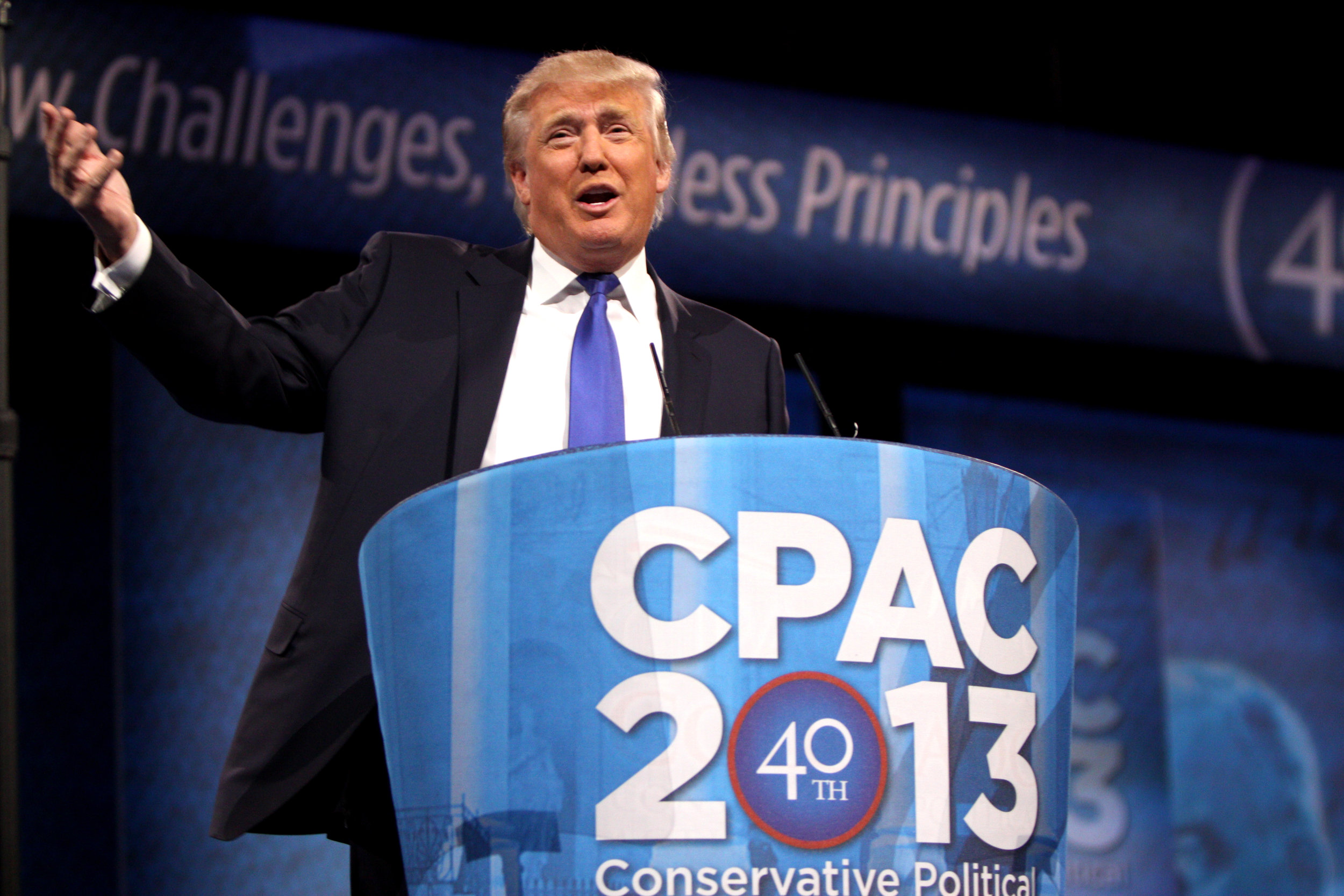

On the morning of March 16th, scientists across the United States exhaled a collective groan. President Trump had released his first budget blueprint, which outlined a plan to slash the budget of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) by $5.8 billion - nearly twenty percent of its total budget. President Trump later expanded these cuts to include $1.2 billion from the National Science Foundation, also supported by the NIH, for the current fiscal year.

The vitriol from scientists regarding the cuts was immediate. In 2016, scientists competed for the precious $31.8 billion granted by the NIH to complete their biomedical research, with only 18% of grants being selected for funding (compared to 30% of grants funded in 2000). The American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology released a statement that the administration was “throwing progress out the window,” while the CEO of the American Association for the Advancement of Science argued that the cuts would cripple science and technology enterprise.

The initial blueprint was vague about how the cuts would be achieved. Specifics included the elimination of the Fogarty Center, established in 1968 with the purpose of supporting global health research, and the consolidation of a research quality agency within other areas of the NIH. Over the following weeks, however, the administration revealed at least one other major target of the cuts – the so-called indirect costs of research.

Indirect costs refer to expenses of a research grant not spent on the research itself; these costs primarily allow for the operation and maintenance of laboratories and research equipment, services such as student health, library expenses, and the existence of administrative personnel. On average, 34% of each grant awarded by the NIH goes toward these costs, although the exact rates are negotiated separately from institution to institution. A report from the Government Accountability Office in 2013 revealed that indirect costs were growing at a faster rate than direct costs of research.

HHS Secretary Tom Price

During a recent congressional hearing, HHS Secretary Tom Price said he was struck by the high margin of grants put toward indirect expenditures. He pointed out that private organizations such as the Gates Foundation limit indirect expenses to 10% of each grant, and noted that if the NIH were to set similar limits they could reduce their costs by $4.7 billion.

It is unclear whether President Trump and his administration realized the political and historical minefield they entered by broaching the subject of indirect costs. Debates over allocations for indirect costs have raged since the 1960s, although they reached a peak in the 1980s during Ronald Reagan’s presidency. In 1950, the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW; now the Department of Health and Human Services) capped indirect costs at 8%. Over the years, as the government ceased subsidizing the maintenance and construction of research facilities, research institutions began to heavily rely on indirect costs to make up these funds. Beginning in 1958, the set limit on indirect costs progressively climbed until it was removed altogether in 1966.

The removal of the cap on indirect costs led to their steady rise, until they became a target of the deficit-reduction battles during the Reagan administration. In 1985, President Reagan proposed cutting the grants awarded by the NIH by 23%. In his thorough history on indirect costs, former President of the Association of American Universities Robert Rosenzweig argues that the flattened growth curve of research funding during the Reagan administration brought research faculty into the political fray. While faculty were against reductions to the NIH budget, they often landed on the same side as President Reagan regarding indirect costs. However, their goals were fundamentally different; the government wanted to limit indirect costs to reduce the budget deficit, and research faculty hoped that limiting indirect costs would expand the limited pot of research funds.

Dr. Rosenzweig notes: “…it always seemed unlikely that money saved by reducing indirect costs would produce anything other than a reduction in the overall research budget.” Indeed, the 26% cap on administrative costs was not established via consultation with scientists or research institutions, but rather because that was the number needed for President Reagan to reduce the NIH budget by the $100 million he needed to support other budget measures.

“The 26% cap on administrative costs was not established via consultation with scientists or research institutions, but rather because that was the number needed for President Reagan to reduce the NIH budget by the $100 million he needed to support other budget measures.”

There have been issues with the allotment of indirect costs. In 1991, government auditors accused Stanford University of spending the funds on non-research expenditures, including flowers, silverware, and upkeep of a yacht. Ultimately, Stanford repaid $1.2 million to the government for its overspending. The debacle ultimately led to the government’s setting a 26% cap to administrative costs for universities.

Which brings us to the events of today. The situation is eerily like that of the 1980s – research funding has plateaued, the government faces a major budget deficit, and research institutions are relying heavily on indirect costs. With these findings, it is perhaps unsurprising that President Trump decided to mimic President Reagan in proposing to cut funding to the NIH. Likely he will find some allies in faculty who believe indirect costs eat into their research funds. However, the goals of President Trump and these faculty are diametrically opposed; one aims to diminish research funding, while the others fight to increase it.

Congress will ultimately decide whether they agree with President Trump’s proposed cuts as they submit their spending plans before the April 28th deadline.