World hunger. Climate change. Animal cruelty and slaughter. Food contamination. Antibiotic-resistant “superbugs.” Imagine if a solution to all these problems lay at our fingertips. Or more specifically, inside our hamburger buns.

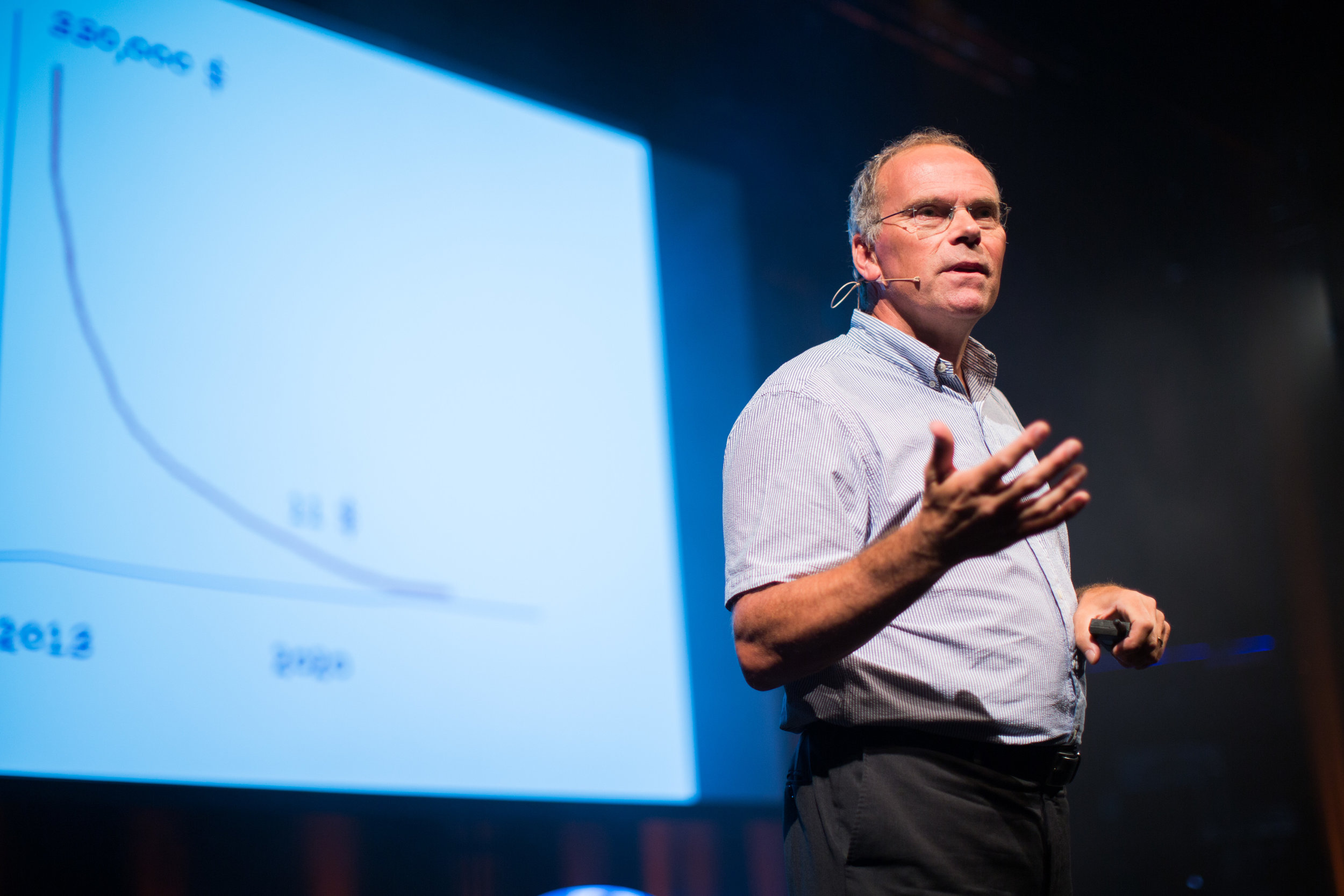

In 2013 Dr. Mark Post of the University of Maastricht debuted the world’s first lab-grown hamburger, the culmination of two years of research and an estimated $330,000 in production costs. Many industry experts at the time – including Post himself – believed that commercial viability would take decades, but supporters were nevertheless quick to hail synthetic meat, also called “cultured meat” or “clean meat,” as the start of a revolution in food, environmentalism, and human health. Now, five years later, the price per patty has plummeted to a mere $11. One critical question remains: will anyone actually eat it?

Both supporters and critics have pointed to particular details of cultured meat production to back their views. The process starts with a small sample of muscle taken from a living animal. Within this sample are cells known as myosatellites, a type of adult stem cell capable of developing into muscle tissue. These myosatellites are isolated and grown in vitro and induced to differentiate into muscle cells known as myotubes. Myotubes are then seeded in a ring-shape on gel scaffolds to accommodate spontaneous contraction, a necessary factor in promoting protein synthesis and tissue growth. Once muscle rings have sufficiently matured, several thousand are compacted together to produce a single beef patty, typically along with cultured fat cells to achieve a more satisfying taste and mouthfeel.

Traditionally, animal blood is a key ingredient for growing cells in vitro. Lab meat startups are working to develop effective blood-free alternatives.

Advocates for such “cellular agriculture” methods point out that, in theory, a single muscle sample could yield an enormous quantity of meat, virtually eliminating the need for animal slaughter and large-scale livestock production. Furthermore, meat could be grown anywhere in the world; a “lab-to-table” trend may even prompt restaurants to develop their own in-house cultures. Reducing traditional animal farming and meat transportation with such a system would be one of the most momentous victories ever achieved in the battle against climate change. According to a 2006 report from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, conventional meat production and transportation directly accounts for 18% of global greenhouse gas emissions. To produce the same quantity of meat in vitro would involve 78-96% lower greenhouse gas emissions, 99% lower land use, and 82-96% lower water use. Additionally, the “animal-free” system would reduce the need for pesticides, antibiotics, and hormones used in traditional meat production. In other words, replacement of conventional meat with cultured meat would not only enhance efforts to halt global climate change, but also improve the health and safety of meat for human consumption and make it easier and more cost-effective to bring meat to populations afflicted by poverty and malnutrition. Good for the environment; good for animal welfare; good for human health. Case closed.

Not so fast, say critics. While some animal welfare advocates praise lab-grown meat, others have called into question just how “animal-free” the production process truly is. The initial tissue sampling, although typically performed under local anesthesia, nevertheless creates some potential for pain without any benefit for the animal itself. In addition, the gel scaffolds on which muscle cells are grown are typically made from pig or mouse tissue, though researchers have made considerable progress in developing synthetic hydrogel alternatives with appropriate textures and elasticity.

The most worrisome detail from an animal rights perspective is also one that threatens to obstruct expansion of the lab meat industry altogether. In order to thrive, cultured cells require a nutrient-rich medium composed of sugars, proteins, and animal blood. Blood derived from non-human fetuses is particularly popular and effective, as it naturally contains components necessary for promoting cell division and growth. In addition to the obvious animal welfare concerns raised by this practice, the enormous volumes of blood required would make industrial-scale production of lab-grown meat virtually impossible. Post and others have been striving to develop animal-free alternatives from plants or algae, while simultaneously attempting to reduce the percentage of blood required in traditional nutrient media or recycle media for multiple rounds of growth. However, industry experts agree that no lab meat products are viable until blood can be removed from the equation completely. At present, this remains a troublesome obstacle both for public acceptance of cultured meat and for its commercial production.

Dr. Mark Post developed the first cultured meat hamburger at the University of Maastricht at an estimated cost of over $330,000. Today the price has dropped to a mere $11 per patty.

Fortunately, a breakthrough may be on the horizon. Shojinmeat, a Japanese non-profit for at-home meat culturing, has successfully developed a yeast-based, blood-free medium, though it is not effective for all cell types. Additionally, l; lab meat startups Finless Foods and Just have both announced plans to be completely blood-free by 2019. Though details about the proposed alternative media are closely-guarded trade secrets, these advances bode well for similar developments and continued improvements throughout the industry.

As clean meat enthusiasts look to the future, the greatest obstacle of all may be one of marketing, not science. Several recent studies investigating consumer acceptance of lab-grown meat have revealed that initial descriptions of cultured meat have a powerful effect on whether or not consumers would be willing to give it a try. Emphasizing similarities to conventional meat and providing information on environmental and health benefits promoted increased consumer acceptance, whereas overly-technical descriptions of the production process and associations with controversial technologies such as GMOs evoked a sense of unnaturalness and disgust – or what Kenneth A. Cook, president of the Environmental Working Group, has dubbed “the ick factor.”

Findings from these studies will undoubtedly have considerable impact on conventional meat producers and synthetic upstarts. A battle over regulations and labeling for lab-grown meat is heating up between the competing industries in recent months that could shape the future of this fledgling area of food science. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced earlier this summer that cultured meat would fall within FDA jurisdiction, yet conventional meat producers continue to push for oversight by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), the organization responsible for regulating traditional meat. Lawmakers thus far have reached no consensus on how to handle the new technology, but in the meantime, “clean meat” is gaining momentum. Startups have garnered high-profile investors including Bill Gates and Richard Branson; even conventional meat heavyweights Tyson and Cargill have joined the game, investing in clean meat startups in the belief that cellular agriculture represents a sustainable and cost-effective alternative source of protein. Tyson president and CEO Tom Hayes, in a statement in which he acknowledges that the move “might seem counterintuitive,” explains that expansion into conventional meat alternatives is a logical course for companies like Tyson, as global demand for protein continues to rise while more and more consumers are calling for sustainably- and ethically-sourced options.

So what lies ahead for this burgeoning industry? Will lab-grown meat save our world, one burger at a time? Someday, perhaps. For now, they’re just trying to make it to our supermarkets.