After death, it turns out that on the cellular level, lifelike processes are still happening.

Read MoreCredit: Nuno Ibra Remane on Flickr.

Credit: Nuno Ibra Remane on Flickr.

After death, it turns out that on the cellular level, lifelike processes are still happening.

Read MoreCredit: Kristaps Bergfelds on Flickr.

Recycling plastics into fuel hits two birds with one stone: check it out at http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2016/06/catalysts-could-turn-trash-bags-fuel

Read MoreWe're all aware of climate change, but one of its consequences that you might not have considered is the spread of parasite-driven disease:

Silk worm cocoons have provided the material for luxury goods for nearly 6000 years.

Most diagnostic blood tests require the samples to be kept stable from the time they are drawn. This often involves expensive refrigeration units, especially if the sample is not taken near a testing facility. Recently, a team at Tufts University in Boston has demonstrated that when silk fibers are dissolved in a blood sample they stabilize the biological components of the sample, which can then be dried and transported at ambient temperatures. This preserves the structure of blood proteins which can then be tested by re-hydrating the sample at a later date.

Read more about this fascinating research in an article from STAT: https://www.statnews.com/2016/05/09/blood-silk-diagnostics/

"Last week, this hellish magic eye popped up on Reddit with no attribution and the perfectly vague caption “this image was generated by a computer on its own.” It became an internet mystery, with guesses springing up across social networks."

via Atlas Obscura

Granddaughter: I have some good news!

Grandma: You're pregnant!!!

Granddaughter: No...no...I'm finally writing my thesis

Grandma: Oh.

"COMING THIS FALL! To arrange a screening at your University or Research Center, visit http://phdcomics.com/movie Haven't seen the first movie? Go to http://phdmovie.com to watch it! Written and Produced by PHD Comics creator Jorge Cham (http://phdcomics.com) and directed by Iram Bilal (http://thefilmjosh.com), The PHD Movie 2 takes a smart and funny look at the world of Academia through the eyes of four grad students."

Below is the trailer for the original movie:

You can watch the original movie for $5 at phdmovie.com!

This isn't terribly Cool Ish, and it goes to show that science education is still something we have to keep trumpeting from toddlers to retirees.

NY State Assemblyman Tom Abinanti (D) of the 92nd district (which includes Yonkers and Tarrytown) introduced a bill to call for the "prohibition on the use of vaccines containing genetically modified organisms."

What this means is that rather than intelligently design an Ebola vaccine using technologies and strategy that are the cornerstone of modern biomedical science, scientists would have to rely on techniques like evolving the virus to be safe enough to be injected into mammals without killing them.

It is unknown what State Assemblyman Abinanti's motivations and fears were that led him to introduce this bill. But it's clear he needs to brush up on his biology. If you would like to teach him about this issue, here is his contact information:

In Albany

LOB 744

Albany, NY 12248

Phone: 518-455-5753

In Tarrytown

303 South Broadway

Suite 229

Tarrytown, NY 10591

Phone: 914-631-1605

Fax: 914-631-1609

via Ars Technica

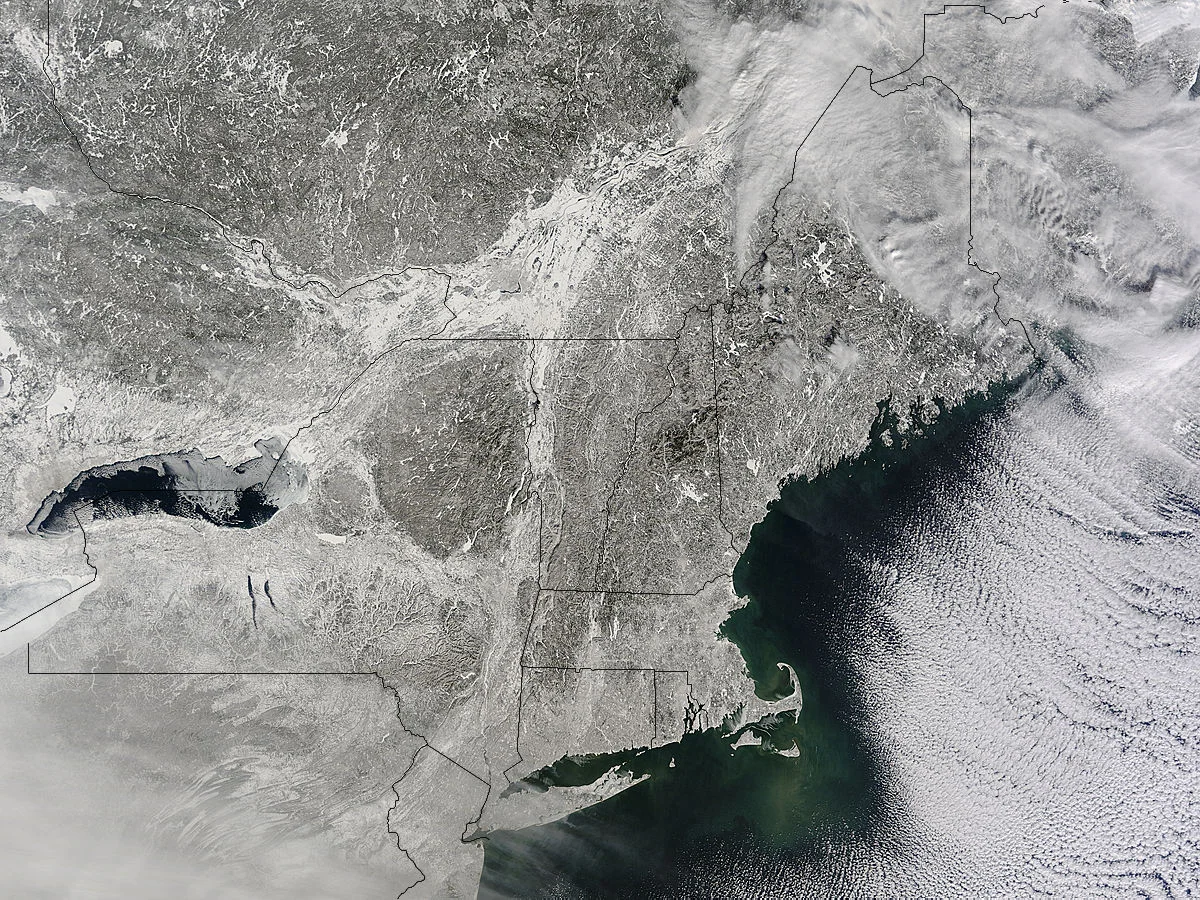

Photo: NASA

The Midwest and the Northeast are currently covered in snow. This will come to no surprise to anyone who lives in these areas and has a window. Those of us who live in these snow-covered areas are also familiar with the gift and the curse that is road salt. The US has been plowing and salting our roads since the 1940s to ensure we don't end up stranded on an Atlanta highway. Unsurprisingly, this generous use of road salt has had an environmental cost.

Researchers at the U.S. Geological Survey published a report where they monitored streams at sites across the US (but primarily located in the Midwest) and showed that:

A study done by Environment Canada in 2001 showed that aquatic organisms (again no surprise there) take the biggest direct ecological hit from the amount of salt we let into our waterways. In a USGS press release, the lead author of the study Steve Corsi said "Findings from this study emphasize the need to consider deicer management options that minimize the use of road salt while still maintaining safe conditions."

via USGS Newsroom

Happy Friday!

As we head off to celebrate the start of the weekend later today, you may well have a friend tap the top of your beer bottle. If you've ever had this happen, you know you better run to a sink or get ready to start hoovering up a bunch of foam if you want to avoid a mess. Generally, one's first thought after this act is how to get your aggressor back when she's least expecting it. However, if you're in a more contemplative mood perhaps you're wondering what's going on inside that bottle that makes it explode in response to such a seemingly innocuous tap. Well physicists at the University of Madrid and Université Pierre et Marie Curie wondered the same thing, and they've got you covered. Here's the abstract of their recent paper in Physical Review Letters.

Image Credit: Flickr user Pixeled79

Abstract: The popular bar prank known in colloquial English as beer tapping consists in hitting the top of a beer bottle with a solid object, usually another bottle, to trigger the foaming over of the former within a few seconds. Despite the trick being known for a long time, to the best of our knowledge, the phenomenon still lacks scientific explanation. Although it seems natural to think that shock-induced cavitation enhances the diffusion of CO2 from the supersaturated bulk liquid into the bubbles by breaking them up, the subtle mechanism by which this happens remains unknown. Here, we show that the overall foaming-over process can be divided into three stages where different physical phenomena take place in different time scales: namely, the bubble-collapse (or cavitation) stage, the diffusion-driven stage, and the buoyancy-driven stage. In the bubble-collapse stage, the impact generates a train of expansion-compression waves in the liquid that leads to the fragmentation of preexisting gas cavities. Upon bubble fragmentation, the sudden increase of the interface-area-to-volume ratio enhances mass transfer significantly, which makes the bubble volume grow by a large factor until CO2 is locally depleted. At that point buoyancy takes over, making the bubble clouds rise and eventually form buoyant vortex rings whose volume grows fast due to the feedback between the buoyancy-induced rising speed and the advection-enhanced CO2 transport from the bulk liquid to the bubble. The physics behind this explosive process sheds insight into the dynamics of geological phenomena such as limnic eruptions.

Full Paper: http://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.113.214501

Vice writer Andrew Iwanicki spent 70 days lying at -6 degrees for a NASA study on bone and muscle atrophy. He describes his experience midway here and at the end here.

Here is a brief excerpt of some of the questions he had during his experience:

Why did I have to drink water out of an open glass, even though at the angle of my bed, it inevitably spilled all over my table and chest? Why did they serve soup in shallow bowls? Why were they serving soup to people in bed anyway? Did any of the staff have any idea what it was like to be stuck in bed?

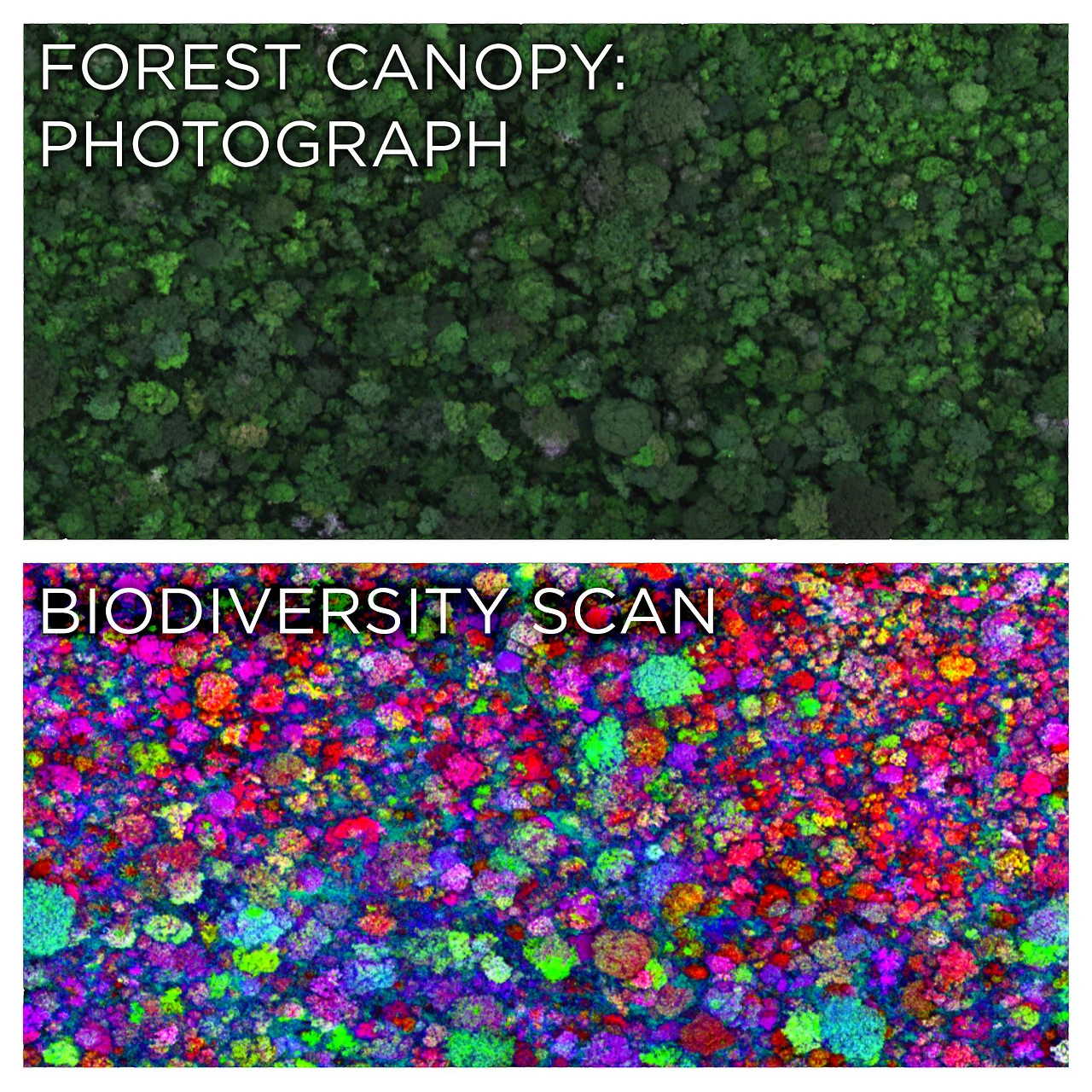

Above: a forest as we've all seen one. Below: the variety of species as denoted by color.

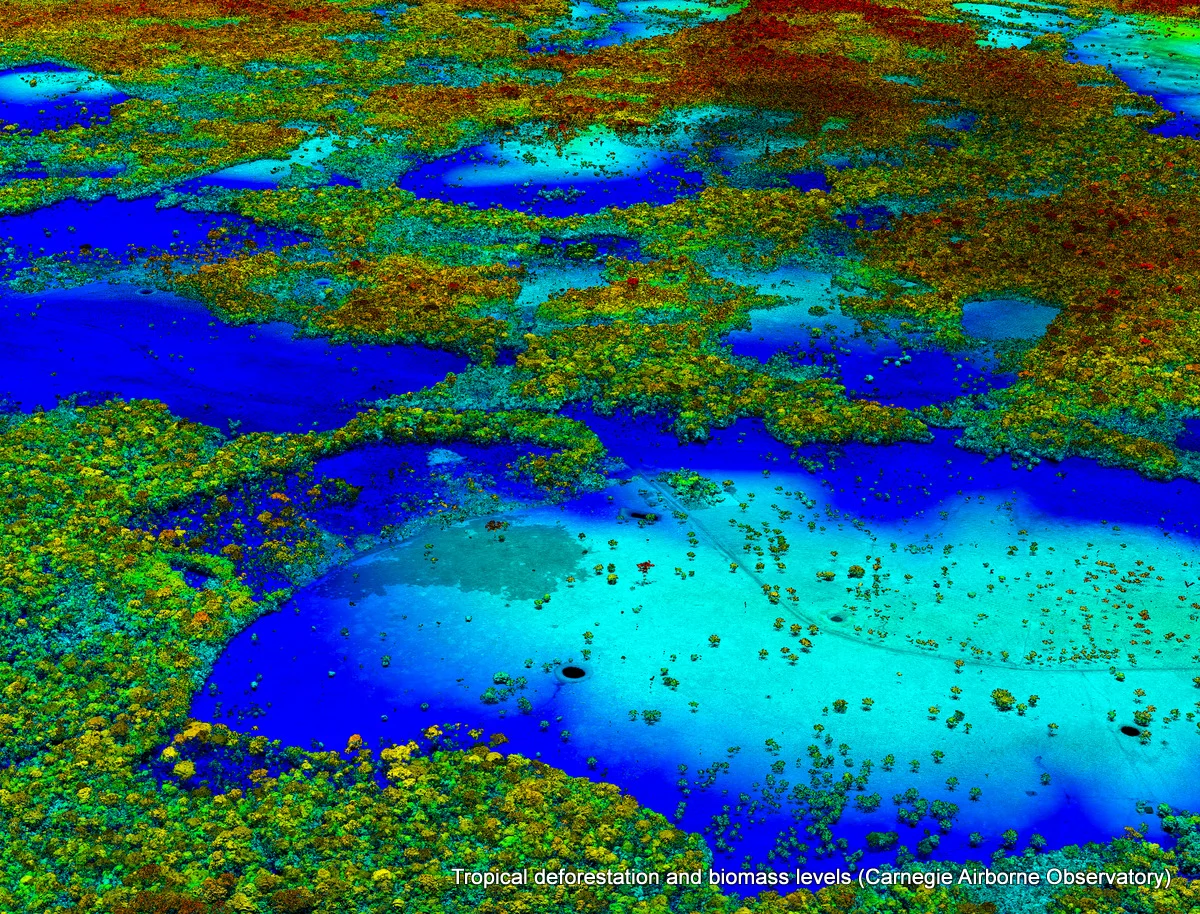

Using a decked out lab in an airplane (aka Carnegie Airborne Observatory), Gregory Asner and colleagues scan forests from the sky with lasers, spectrometers, and other tools to generate 3D maps that not only capture every plant down to their branches, but also differentiate which species they are.

Asner and his team have mapped out a slew of landscapes (which you can see the results of here). According to NPR "on one occasion, he and his team mapped more than 6,500 square miles of the Colombian Amazon at night — about the size of Connecticut plus Rhode Island — flying with all their lights out to avoid being shot at by the FARC, the Colombian rebel force."

If you're interested in this sort of work, Asner is looking for volunteers. You can find out more at the Carnegie Airborne Observatory website.

Tropical Deforestation and Biomass Levels. Source: Carnegie Airborne Observatory

via NPR's Science Tumblr Skunk Bear

Kids these days....

Taiwanese researchers have sampled river and waste water samples before, during, and after a 2011 pop musical festival in Taiwan called Spring Scream. According to the authors of the study, this festival is "notorious for the problems of drug abuse and addiction."

Their study shows that the festival runoff causes a spike in compounds such as acetaminophen (Tylenol), caffeine, pseudoephedrine, MDMA (ecstasy), and ketamine. Other studies mentioned in this article have also shown increases in controlled substances (e.g. MDMA, cocaine) in water samples during New Year's Eve celebrations, graduation parties, big dances, and just weekends.

The authors couldn't characterize the local ecological impact of the surge of these compounds, but note that such studies could be concerning both for the environment and for the festival attendees.

via Ars Technica and Environ. Sci. Technol.

SpaceX's Falcon 9 rocket successfully launched and delivered it's Dragon capsule to the International Space Station. Rather than a hard landing back into the ocean (like normal rockets do), the Falcon 9 rocket attempted a soft landing on a barge floating in the Atlantic (the first attempt of its kind). Initially, CEO Elon Musk said there was a 50:50 chance the landing would be successful.

The attempt was, in fact, nearly a home run. However, mere seconds before landing, the rocket ran out of hydraulic fluid in the fins that steer the rocket as it descends. This caused it to hit the barge and perform a Rapid Unscheduled Disassembly (aka explosion). According to Musk, the next launch is scheduled for the next 2 to 3 weeks. This new rocket will have 50% more hydraulic fluid. So at least it should "explode for a diff [sic] reason."

Musk hopes that successful soft landings will allow for quick and cost-effective reuse of rockets, making space travel significantly more affordable and feasible.

From centuries-old specimens to entirely new types of specialized collections like frozen tissues and genomic data, the Museum's scientific collections (with more than 33,000,000 specimens and artifacts) form an irreplaceable record of life on Earth, the span of geologic time, and knowledge about our vast universe.

The American Museum of Natural History has been collecting artifacts and specimens since 1869. As of 2014, it has amassed over 33 million objects (7.5 million of which are wasps, apparently). A vast majority of the objects are preserved and stored away from the public eye, but are still used for research purposes.

To showcase a bit about what goes on behind the scenes, the museum has recently started a monthly series called Shelf Life (the first episode of which is above). Each installment is only about 5 minutes, which feels too short for how interesting their work is.

Darrel Frost, curator in the Department of Herpetology, describes nicely his take on all the objects the museum has in its archives:

Photo: Martin Griffith, Flickr.

Graphene is slated to be the material of the future, but how much of this is hype? The New Yorker's John Colapinto explores graphene's origin, possible uses, and expectations.

Check out his article in the Dec. 22, 2014 issue.

In the December 5th issue of Science, Kenneth Catania of Vanderbilt University published how an electric eel (Electrophorus electricus) uses its shocks to find and catch prey, the details of which were previously unclear given the speed at which an attack occurs.

Red flashes indicate electric pulses. The prey is stunned shortly after the attack starts.

Using a high-speed camera, Catania found that if an eel detects prey, it can unleash a volley of electric pulses which causes its prey's muscles to contract so rapidly (within a few milliseconds) that they lock up, leaving the prey vulnerable and ready to be eaten.

In more complex environments where the prey is hidden and motionless to avoid detection, the eel can emit a few pulses (doublets or triplets) causing the prey to twitch and make its location known. Detecting this movement, the eel then launches its attack volley to stun its prey before eating it.

For more on this, check out this video, the Science article, or Carl Zimmer's New York Times article.

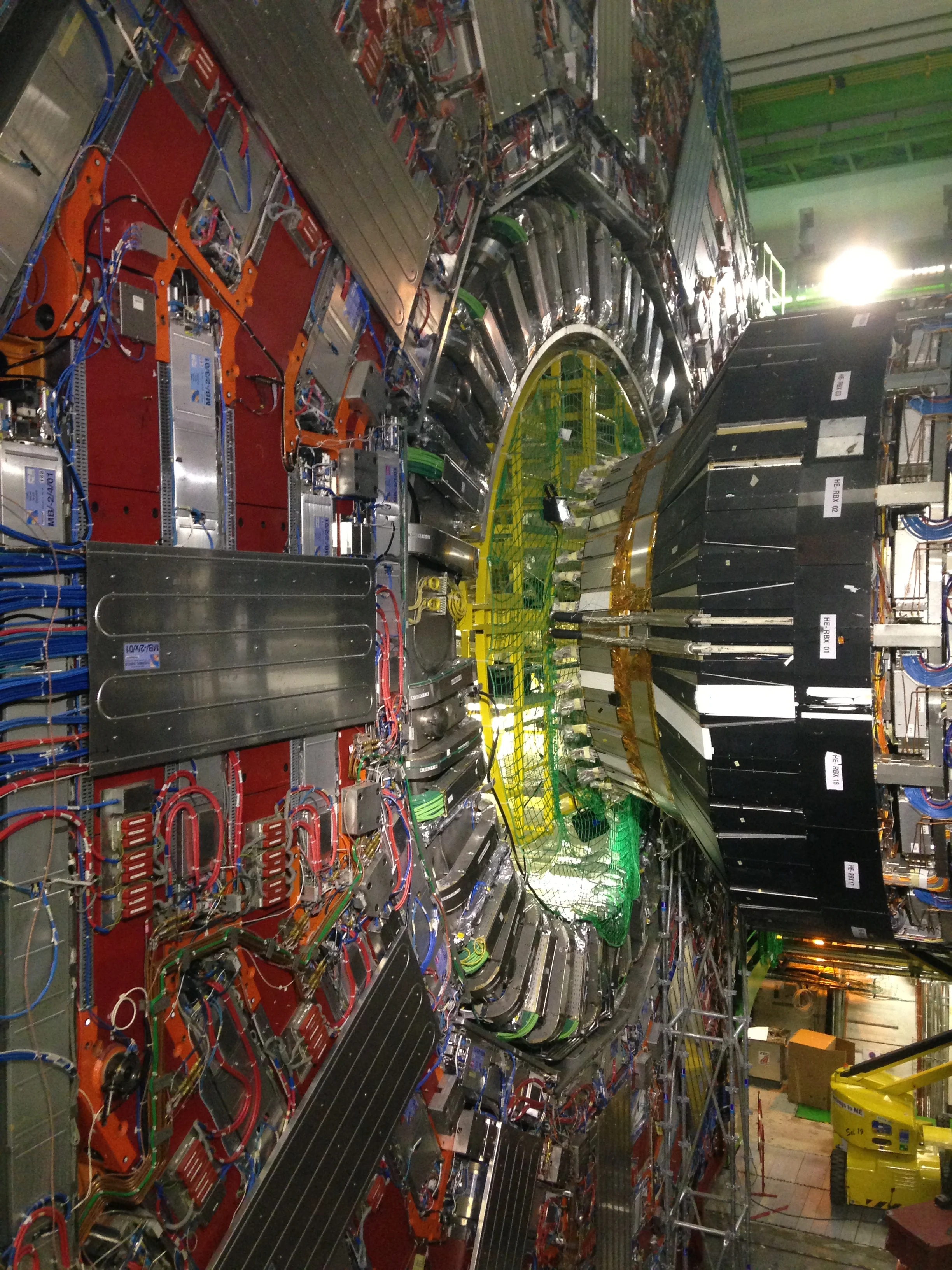

Theoretical physicist David Kaplan explains the importance of funding the Large Hadron Collider (LHC).

Watch the clip here (via Gizmodo) or in the documentary about the LHC, Particle Fever, on Netflix.

Or just read this transcript:

The question by an economist was,"What is the financial gain of running an experiment like this and the discoveries that we will make in this experiment?" And it's a very, very simple answer.

I have no idea.

We have no idea.

When radio waves were discovered, they weren't called radio waves, because there were no radios. They were discovered as some sort of radiation.

Basic science for big breakthroughs needs to occur at a level where you're not asking, "What is the economic gain?" You're asking, "What do we not know, and where can we make progress?"

So what is the LHC good for? Could be nothing other than just understanding everything.

The Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) detector on the LHC. Photo: Wikipedia

Photo: NASA

A photo taken from the Orion spacecraft as it was ascending to its maximum 3600mi altitude. You can still watch it return to Earth live on NASA TV (until about 11:30 am EST today).